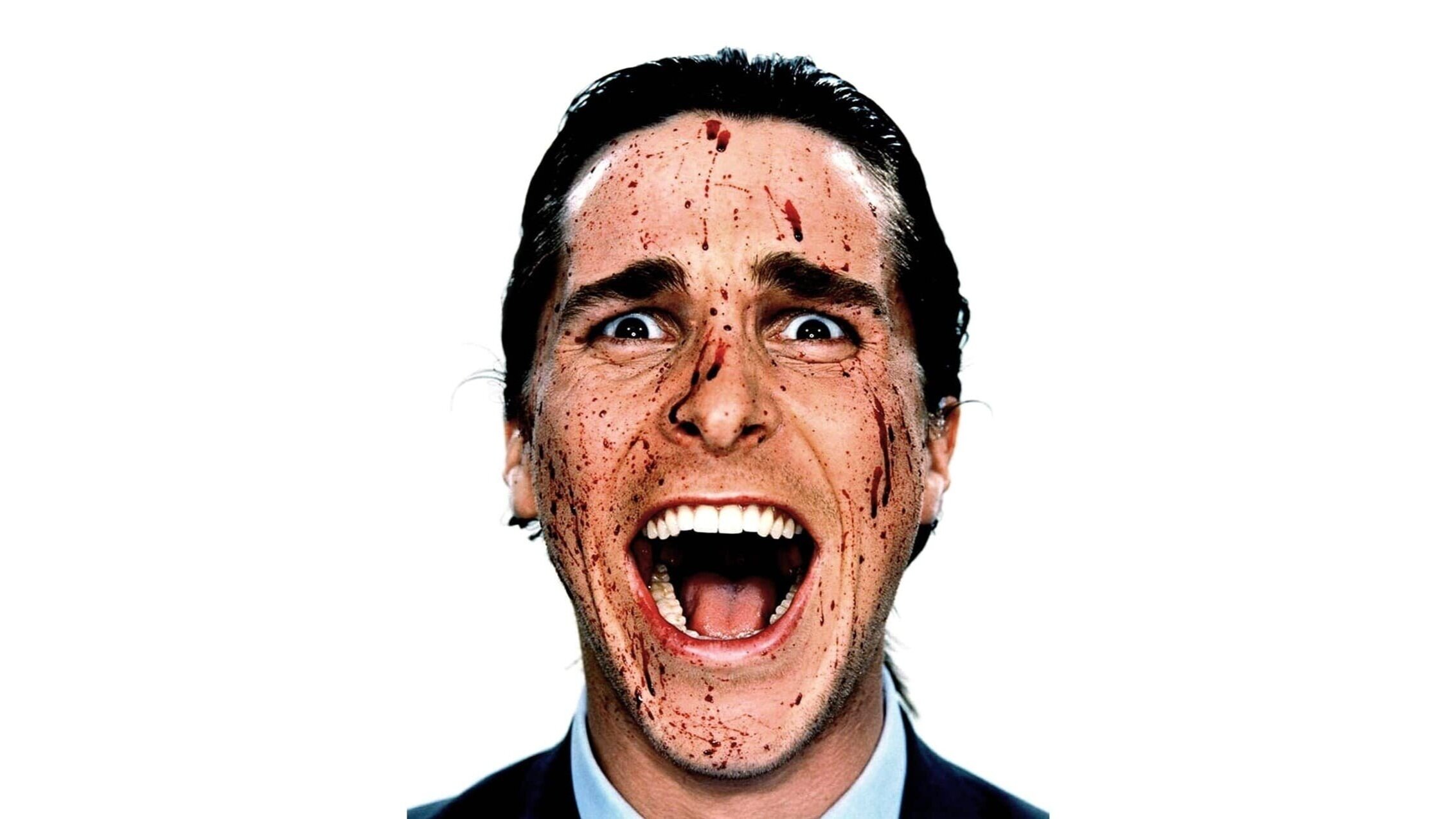

Death by Adaptation: American Psycho

Lions GateHow crazed must one be to work on Wall Street? Bret Easton Ellis wished to figure that much out, at least, with American Psycho. His controversial 1991 book dabbles in the days of Patrick Bateman, a man painted as an egotistical glimmer of high-society. He brushes shoulders with the best, drinks at fancy restaurants, idolises the business moguls of the time, and has a penchant for murder. Adapting that to the big screen proved just as controversial for director Mary Harron, who presents Bateman's upper-class living, expensive lifestyle and murderous intent with a tinge of tongue-in-cheek satire that Ellis provided just as well in writing.

Where Bret Easton Ellis wished to critique the egalitarian halls of Wall Street and the flashy style of living, Harron explores the impact of such a lifestyle. Gone are the glitzy paragraphs yearning for attention with designer suits, fitted jackets and accessory choices, in come the notes of paranoia and anguish washing over unhinged protagonist Patrick Bateman. At least Ellis and Harron are in agreement over one topic: what Bateman represents and his importance within American Psycho. Controversy is the deep nature of this project, and as it swept up literary freaks and shocked audiences alike, the similarities between book and film become ever clearer.

One of the key notes to pick up on from both versions of American Psycho is that of Bateman. He is – alongside many plot points – a graceful translation from page to screen. His descent into madness is a reflection of conformity in both pieces, but it is handled with far more tact and interest in the book. Naturally so, but that does not stop Harron from having her own spin on what it means for the mind of Pat Bateman. Visual vanity is at the core of American Psycho. All those slick suits and stylish fantasies are founded on the idea that Bateman is a torchbearer for quality. He is represented as such in both the book and film, often judging what people wear and why they choose to wear it.

He is disgusted by the simple, personal touches people choose to make. American Psycho is so focused on this that its ethical dilemma soon becomes what we think of the fashion and attitudes of the time, rather than that of the bloodlust Bateman has. He is a man without remorse, and the visualisation of Ellis’ darker periods within the text are delightful and horrifyingly well represented. Ellis has the benefit of vivid detail and description, which depict truly disgusting acts of violence toward those who do not deserve it. It is one of the few areas where American Psycho differs between book and film. Repetition is key for both, but the detail presented to the hyper-violence is chilling either way. Ellis’ craft has isolated incidents: the disappearance of Paul Allen, the description of Huey Lewis and the News, the iconography of the time. These isolated pockets are beautiful, disconnected, yet perfectly sensible descriptive indicators of the time Ellis brings to life.

Where Harron adapts – and even improves with – these moments is their blurring together. Readers have to do so anyway, so seeing its visualisation pair the hyper-violence, the self-preservation ideals that Bateman represents as well as hearing the bands and songs Bateman monologues of in chapters of the book is a collectively successful realisation of American Psycho. Its intent is preserved as a cutting criticism of the lifestyle Bateman perseveres through, but the mockery and dejection comes from how seriously he takes it, rather than from crummy jokes or cheap pops. It is a world far, far removed from the majority of readers or viewers, and because of that, the murky depths of the world around Bateman are far more believable.

Inevitably, though, what the adaptation lacks is the subtlety and recurring conversational points. Ellis was no stranger to the concepts that burrowed deep into the mind of everyone within the 1980s. His discussion of the AIDS crisis, popular bands like Talking Heads and Genesis, whatever was suitable table talk in that decade is lacking in Harron’s adaptation. Perhaps that is because it is here Harron tries to make the piece timeless. She carefully selects the dialogue that is lifted from the book, replicating a surprising timelessness. Huey Lewis and the News may feature on the soundtrack of the film, but it is a song that will never die. It lives on in infamy, immortalised by the very film that took a gamble on it. With the book, there is an iconographic desire felt for the dying embers of the 1980s, where with the film, Harron strives to make her piece timeless, with broader strokes for the attitudes, costumes and conversations, which could be heard or found in those Wall Street walks of life.

Harron's active attempt at carving out an ageless iconography works because of the casting and the cultural choices made. Armani, Jared Leto and Huey Lewis are all identifiable pointers in the modern world, whether that is through an inherent nostalgia for other projects or a definitive love for them within the lives of the reader or the viewer. The lack of specific, timed dates like the AIDS crisis within the Harron piece is not a drawback but a bold chance to take a piece of literature inherently linked with a piece of history, and to cut it off in the hopes of making something that can live on past its newsworthy pointers.

That is the dependability of both book and film, though, and with American Psycho, the blur of iconography and surrounding has its own separate intentions in either form. Imagery is the severest form of flattery for Bateman and company, it is why the book dedicates itself to the fancy dishes, the slick suits and the company these men and women find them in. That is more important than the apparent psychosis Bateman finds himself hurtling through, although Ellis and Harron handle both marvellously, the real beauty and interest of the book is how deceitful its characters are of one another, how fearful they are of being in the wrong company, and both do well to describe why it matters. Harron less so, though, as she wishes to focus on the crux that will leave audiences shocked: the killings Pat Bateman carries out.

A great point of discussion for many fans of book and film is whether Bateman is actually conducting these murders or if they’re just part of a sick and twisted fantasy. Both pieces adapt this with clear skill, utilising the benefits of visuals or the written word. For Harron, the bleak realisation of murderous rage is captured with a necessary dark tone, one that highlights Bale’s performance as unhinged. Yet even in those moments, much like the book, Bateman is still classy. The book rounds off these moments with dialogue of threatening desire, replacing what audiences can assume is a nonchalant reply to a boring conversation on tie etiquette or drink reservations. Nobody reacts to what Bateman says, because he simply doesn’t say it. Or does he? With the film, it is harder still to negate the fantasy elements, and because Harron slips them so seamlessly into the narrative, sifting through what is fact and what is fiction for Bateman’s life is far more difficult than the written world Ellis offers.

Either way, whether Bateman did it or not, American Psycho is a strong text and a strong film. The two are guided well by excellent visionaries. Ellis’ delightful criticism of the Wall Street workhouses and the cocaine that coddled all those at the heart of it may be different to the paranoid charms of Harron’s filmed adaptation, but the effect is still the same. Bateman is never meant to be reconciled with either his friends or the audience, but the charisma he dishes out in the film, and the commentary he offers in the book, make him devilish, narcissistic company. Audiences are tied to the man both in the film and the book, but there is a guilt-ridden realisation presented by Ellis and Harron, that the lifestyle he leads would push him to this type of murderous behaviour. They play the blame game mightily well. Can an audience sympathise with the man that murders his way through Manhattan? His business card isn’t eggshell white. Does the audience know how that feels?