NOTTING HILL: The seminal romantic comedy of the 1990s

UNIVERSALIt Is 1999. Tony Blair’s in Downing Street, the Spice Girls hog radio waves across the country, and the screen-romance explosion in the aftermath of Titanic is still refusing to sink. Oxford University-alum, Richard Curtis, little-known to global audiences besides his penning of Blackadder or Bean, has erupted into the limelight following the release of Four Weddings and a Funeral in 1994, and its $245 million box-office haul.

Lauded by Variety as ‘a deliciously heady mix of dry wit and ribald farce’, it defied cynics by quickly solidifying itself into the zeitgeist of the mid-90s pop-culture, creating a star out of the stammering, floppy-haired Hugh Grant and forcing open a market for British comedies on an international scale (The Full Monty). Audiences waited with anticipation for another plunge into the world of Curtis whimsy. He quietly prepared his follow-up, promising to build on the formula he had concocted through Four Weddings with something more witty and charming than before.

It was in this year that the purveyor of warm and fuzzy released his magnum opus. Enter the most famous actress in the world: Julia Roberts (riding high off Pretty Woman and My Best Friend’s Wedding), the most famous actress in the world, playing Anna Scott, and you have half of Notting Hill. It is a tale of boy meets girl spun on its head, with the ensuing dizziness persisting throughout various infatuations and heartbreaks until its Elvis Costello-scored conclusion. In the years that followed, its star seemed to wane somewhat, drowning beneath the dogpile of turn-of-the-century genre hits (The Matrix, The Phantom Menace, The Sixth Sense).

A casualty of Curtis’ continued success occurred; it found itself disappearing into the crack between the landmark Four Weddingsand 2003’s ensemble guilty-pleasure Love Actually, despite superseding both at the box office. Notting Hill has become the neglected middle-child of Curtis’ filmography, damaged further by an initially mixed reception. While some called it an inferior Four Weddings rehash (Village Voice condemning it as the ‘same movie, only worse’), supporters like Entertainment Weekly described it as a ‘blithe and exhilarating romantic comedy’. Notting Hill deserves to be accepted not only as Curtis’ most influential contribution to the silver screen, but as one of the definitive romances of the modern era.

The film’s triumphs are not sole products of the script. The lead performances enhance its potential. Grant plays the idealised incarnation of the starry-eyed sentimentalist we have all been at one point in our lives. William Thacker is hardly a silver-tongued charlatan, but he possesses the bumbling charm and niceties we all aspire to have ourselves, moulding a relatable character from the get-go.

As his opposite, Julia Roberts gives Anna Scott a pseudo-regality. She is in the media-centric fictionalised reality of Notting Hill, or would be in our own. This exaggerates her infeasibility, only cemented in a passing comment from Thacker’s partner-in-crime, Max (Tim McInnerny), ‘you know what happens to mortals who get involved with gods’. Her intimacy around Grant compared to this nonchalant public figure highlights the tragedy of fame nullifying emotion, hinted at in a press junket scene which, while played for laughs, underlines the heart-breaking reality of how this kind of infatuation would eventually result. Nonetheless, this help creates a nuanced performance that avoids shallow superficiality.

It is also no coincidence that Scott is an American. The sense of foreignness hinted at with Andie MacDowell in Four Weddings is further explored here. Curtis uses this culture clash to expose their respective stereotypes, the free-spirited American and the overly conservative Brit. It almost mirrors the comparison between Hollywood and British cinema, the latter always in awe of the grandiose former. This adds a spectral likeness to Anna’s presence, as though she can come and go, disappear as quickly as she arrived which, to the peril of our protagonist and the audience, she often does.

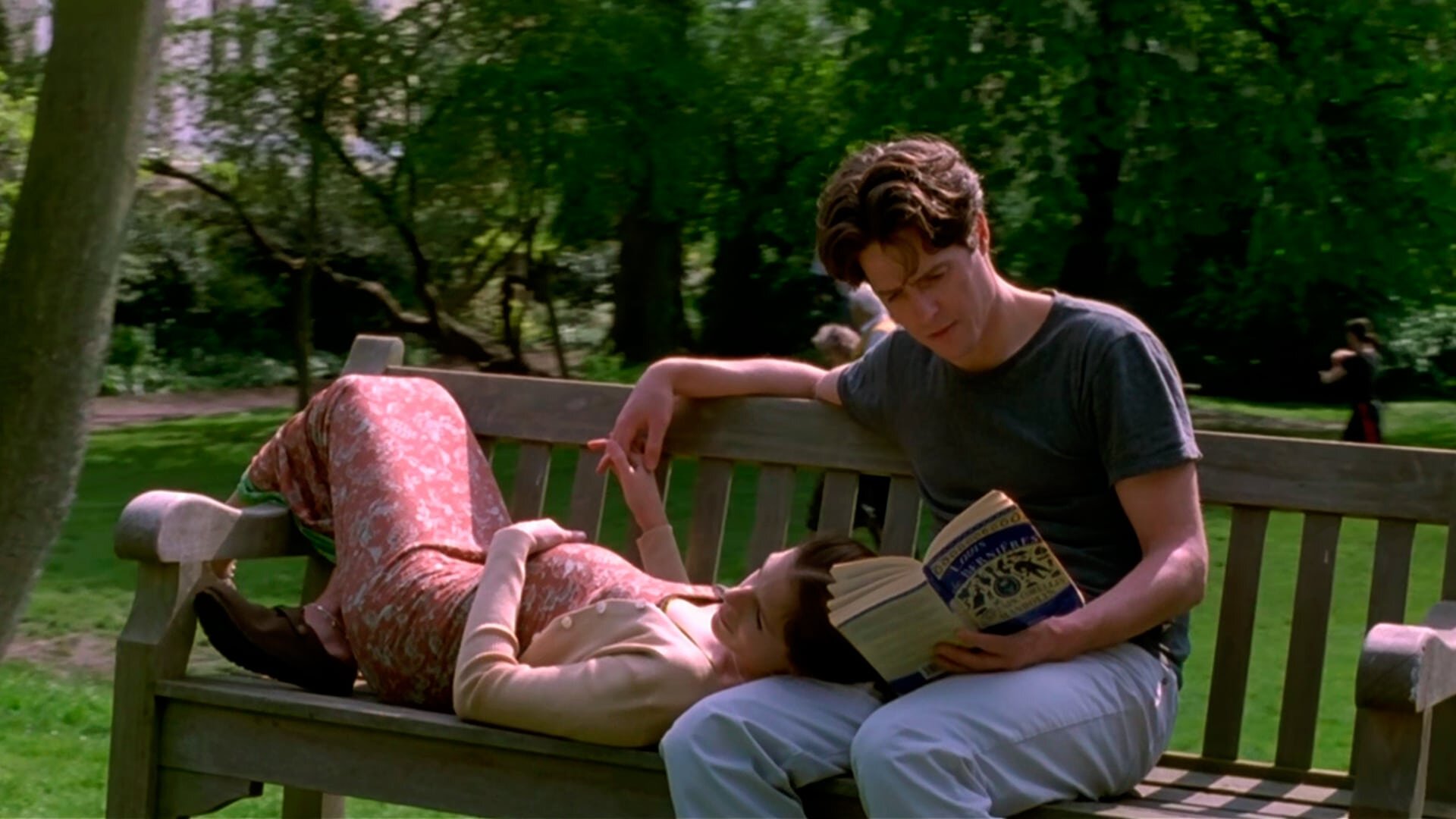

The two play off one another very well, Roberts even beginning to adopt aspects of Grant’s mawkish underdog charm as the narrative progresses, ‘happiness is not happiness without a violin-playing goat’. Their on-screen chemistry is the ideal incarnation of what Curtis has on the page, a symbiotic recreation of his imagination that is all but absent from modern films of its denomination.

Many facets contribute to the creation of this overarching relationship, the most crucial of which being the concept of romantic unattainability. Feelings of affection toward one another that go unanswered are grounded in reality, and it is this familiarity that serves as the infrastructure for the central romance. As a result, Notting Hill can be seen as a hopeless romantic’s wish fulfilment. It takes these authentic emotions and uses them to shape a story that defies the impossibilities of reality to create something unique and compelling.

There is an old line from Annie Hall, where Woody Allen turns to camera and says ‘you know how you’re always trying to get things to come out perfect in art because it’s real difficult in life’, which seems to be the prevailing mantra for Curtis and his audience in Notting Hill. The likelihood of a relationship between an astronomically famed actress and a middle-class bookseller blooming, let alone succeeding, is minuscule, but Curtis uses the filmic medium to realise what could happen, not what would.

This being a Richard Curtis film, the supporting players that surround the main plot leave more than an impression. On another level, they help to bring the essence of Notting Hill to the forefront; it is a film about romance of all kinds. There is a rear-view romantic history between Thacker and Bella (Gina McKee), an immovable bond of marriage connecting Bella and Max, and even the impromptu engagement of Honey (Emma Chambers) and Rhys Ifans’, Spike, the ultimate comic relief.

This friendship group is a dynamic refined from Four Weddings, even taking inspiration from its own blood relative by updating the ginger-haired unlucky-in-love sister. On one level, this helps to humanise Thacker, surrounding him with people who suggest a history without expository bluntness. Furthermore, it is emphatic of the importance love carries. For a band of social misfits facing infertility, loneliness and dissatisfaction – topics that would be handled much differently in the hands of other filmmakers – their congregational moments help them forget these shortcomings, even making them the brunt of the joke.

These people are content with life’s imperfections, because joy springs from their relationships with each other. They do not exist to fill time between Thacker and Anna’s moments, but to enhance them and add another subtext to the narrative entirely. It just helps that Curtis writes them with such charisma and wit that these intentions are translated subconsciously.

Doing justice to its title, Notting Hill’s romanticised version of London bears almost no resemblance to the disparate reality. The city depicted here is a fantastical offshoot where strangers kiss on doorsteps, paparazzi outnumber the population of a small country, and travel-book salesmen reside in Grecian-white flats overlooking the vibrant marketplaces and moonlit parks. London, to Curtis, might as well be Wonderland to Caroll, albeit one more recognisable, if only slightly.

Criticisms have since arisen surrounding a middle-class focus, a complete ignorance of the city and its people as a whole. The action does take place in and around an extremely multicultural suburb, which, when considering the lack of diversity on screen, is alarming. This does date the film from a modern socio-political perspective. Despite the unfortunate reality, this is a story about a relationship. It shuns the responsibility of trying to replicate the environment in which it is set. It is not remotely political, maybe a charge that could be levelled in all of Curtis’ work. This ignorance proved sourly evident in his 2009 effort, The Boat that Rocked.

A product of the 1990s, cheese and soppy pulp do rear their ugly heads alongside these cultural oversights, a regrettable sign of the times. During the closing of the second act, there is stunning long take in which Thacker wanders down Portobello Road as seasons change around him. This enforces understanding that Notting Hill is an urban fantasy, complete with storybook opening narration, where Thacker describes his ‘strange half-life’, and they-all-lived-happily-ever-after ending. The central romance is, unlike its setting, undoubtedly genuine, perhaps just viewed through rose-tinted glasses.

The most quotable remnant of Curtis’ screenplay is Roberts’ heart-breaking no-holds-barred monologue: ‘I’m just a girl, standing in front of a boy, asking him to love her’. It encapsulates the objective of the film, a love story through and through. When seen from this point of view, Notting Hill inspires hope that maybe, just maybe, it is not such a fantasy after all.