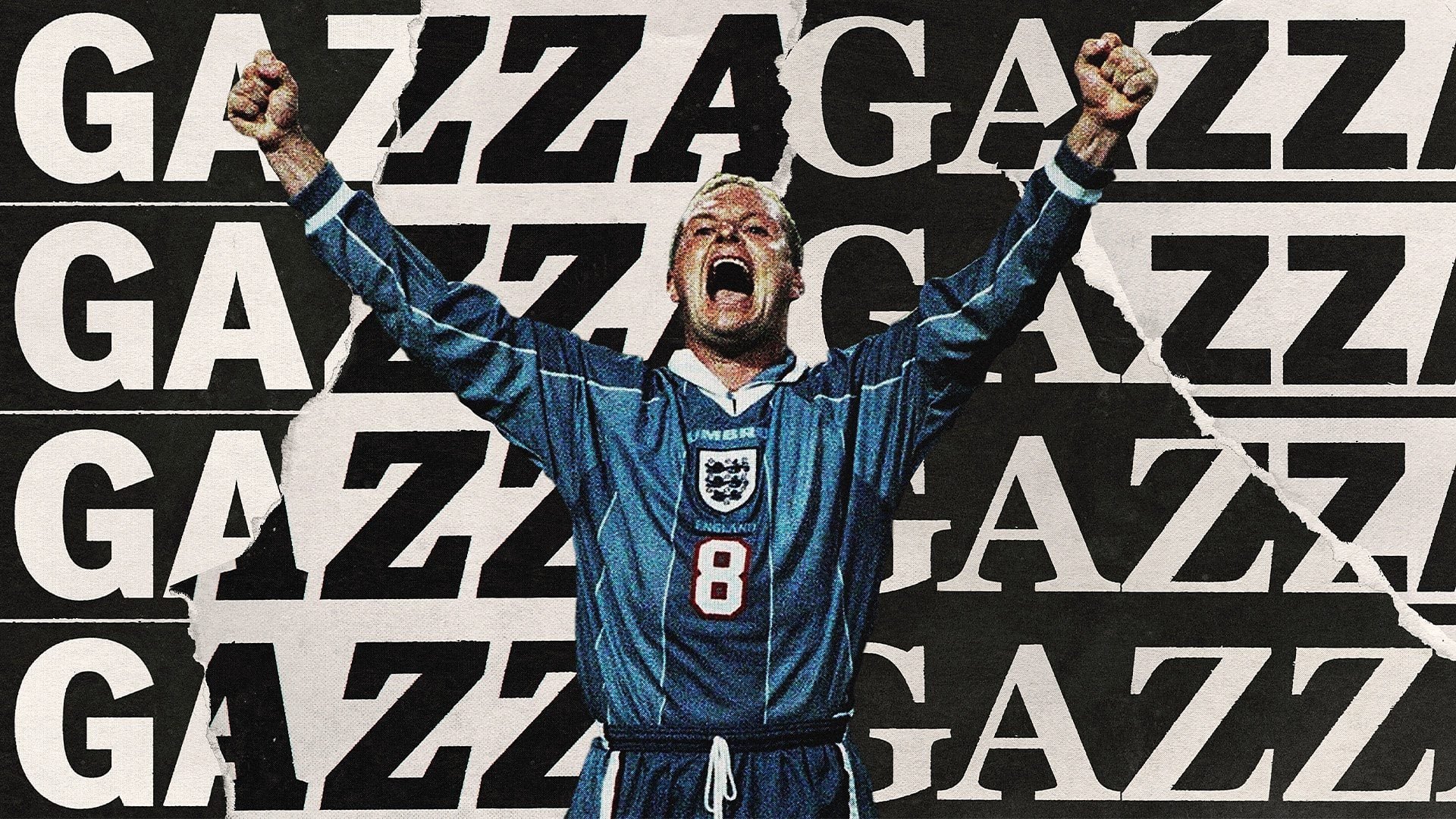

Gazza

BBCBeyond that moment during the World Cup and the peddling and puncturing of personal life in the tabloids, little can be interpreted about Paul Gascoigne without the shroud of controversies, highs and lows that lingered, and everything in-between. The intricacies and relationship between professional footballer Gascoigne and the press was a difficult one. One that needs to be analysed, formatted correctly and dived into deeply. Gazza tries that. It truly, truly does. No bad form to be had, a genuine attempt at understanding a wasteful dynamic between hounding from the press and a troubled man with a need for some layer of privacy to work on himself.

To pass commentary on it with the benefit of hindsight makes it easy, but Gazza does a good job of transporting a new generation to this horrifying series of developments. Gascoigne is at one point compared to Jack Nicholson from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and that does absolutely nothing, but also as much as it can, to set the pace for how Gascoigne was perceived before the drive for publication of his personal life in the press. His personality oozes through the feature at least, and with the help of a variety of former teammates, pundits and family members, a good picture is painted of Gascoigne. But there is a difference between painting a picture and understanding it. Where the former works so well, the latter is lacking quite often. It relies more on prompts of the soundtrack and the scattershot use of visual highs and lows than anything that could linger on the mind for much longer than the time it takes to see another iconic Gascoigne goal.

Not as intimate as My Name is Francesco Totti, not as balanced as Sir Alex Ferguson: Never Give In. Football documentaries will always have a place to tell more about legendary players, but the whiplash effect of Gazza comes rather quickly and clearly. Thirty seconds of building up who Gascoigne was, a quick flash of Newcastle United and director Sam Collins does just what the press did. Straight onto the personal life of Gascoigne and the same repeated note of bodiless voiceovers saying he was a “football genius” and chastising the tabloids for following the same line of reasoning and thought that Collins’ work here does. Obviously, no damage is done by Gazza, but it digs up some dark moments with no exceptionally grand reason for doing so beyond noting that it happened. It is hard to corroborate some moments and points Collins makes when relying on former journalists and players so intimately invested in their own side of the Gascoigne saga. Asking journalists of The Sun what they think of past stories is not going to hold much balance.

Any documentary that can help someone learn something more about a bombshell topic that has since faded will always have its place. Gazza has a tough run at times, spiralling into a two-hour vehicle that hopes to capture any and every detail it can from a busy and interesting period. It still feels a bit ghoulish even decades on, to take a backseat in the car crash that was the relationship between Gascoigne and the media, but doing so feels like a history lesson with whiplash. Gazza marks all the right notes of local pride for a legendary player of the game, but glosses over some of the darker periods, the lower notes of playing for Rangers or Lazio after the high of Premier League football. The scrutiny Gascoigne faced is unforgettable and, by the looks of Gazza, unforgivable.